William Rollan: HMS Leviathan

Convict handcuffs [i]

In the words of his great-great-great-grandson, convict William Rollan was a ‘violent drunken thief’.[1] Les Bursill OAM, a specialist anthropologist on the Dharawal people and a direct descendant of William and his Aboriginal partner Susan Ellis, recalls that family members had ‘always known’ about William’s aberrant behaviour in the latter part of his life. [2] However, Les’s family is equally well aware that William became a model citizen, hard-working and popular among his local community. It was only in William’s final years that his battle with alcohol began, leading to his incarceration and eventual demise in a lunatic asylum.[3] Surrounding these very personal recollections are many official records that offer insight into William’s life as a convict and his transition from indentured convict to land selector.

Born to parents John and Anne Maria Rollan in Lambeth Surrey England around 1818, William’s formative years were a time of dramatic upheaval in England.[4] The Industrial Revolution marked major efficiency developments in agriculture and mechanical processes, altering much of daily life. Many people flocked to cities to find work, but mass production of goods caused significant job losses. Workhouses for the poor were overcrowded and often people turned to a life of crime to avoid starvation.[5]

Powerloom weaving, 1835 [ii]

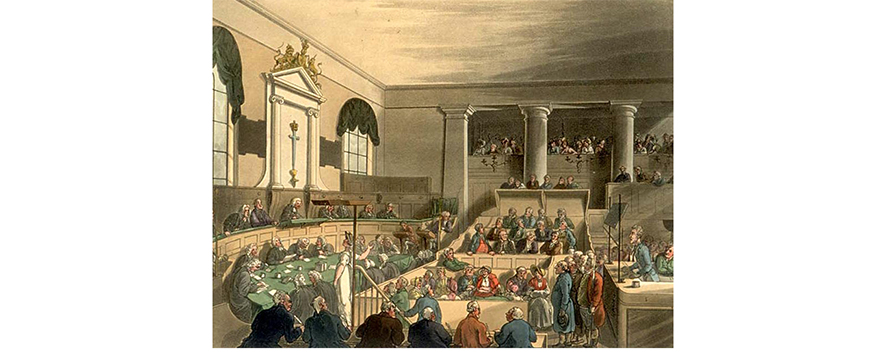

With a steady income, William’s family was part of the new middle class tier in society and not likely to starve. As foreman at the Maltby brass manufactory, William’s father earned a regular wage; William worked there too, albeit without the owner’s permission. Greed, therefore, appears the reason for the theft from Maltby manufactory of four valuable ‘bearing-brasses’ for which William was tried at London’s Central Criminal Court (affectionately known as the Old Bailey) in 1835.[6]

Courtroom, Old Bailey [iii]

The stolen brass was too heavy to be moved by someone acting alone. Although William’s father was the likely accomplice, he diverted attention away from himself by reporting the broken door, leaving William to shoulder the blame. On 23 November, William was found guilty and sentenced to ‘Life with transportation’, the severity of the sentence due to the value of the stolen brass.[7]

From incarceration at Newgate Prison, William was transferred to the prison hulk HMS Leviathan, a former warship permanently anchored in Portsmouth, Here, despite being fed a diet low in vegetables and high in meat, William was proclaimed ‘Healthy’.[8]

Early prison hulk, England [iv]

Read more about HMS Leviathan here

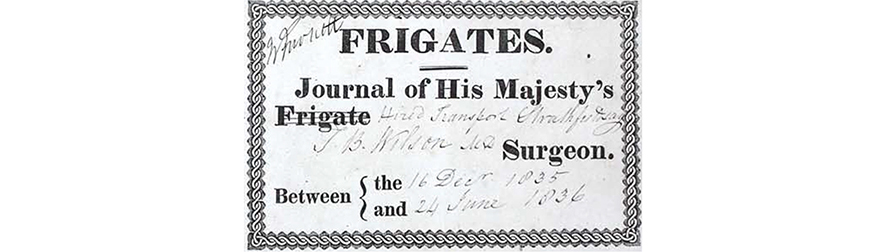

On 6 February 1836, some 3 months after his conviction, William was moved to the ‘Hired Transport’ convict shipStrathfieldsaye along with other male convicts for the voyage to New South Wales.[9] Soldiers were present on the male convict ship to maintain order among the prisoners; on female convict ships there were no soldiers. Thomas Braidwood Wilson M.D., the Strathfieldsaye Surgeon Superintendent responsible for maintaining the good health of the prisoners throughout the journey, kept an extensive logbook, writing detailed notes on individuals exhibiting serious illnesses. William, fortunately, was not among them, although he may have suffered from ‘Rheumatismus’ or ‘Apoplexia’, the most common general afflictions suffered by the ship’s company.[10]

Cover label, Surgeon Superintendent's Journal, Strathfieldsaye, 1835-1836 [v]

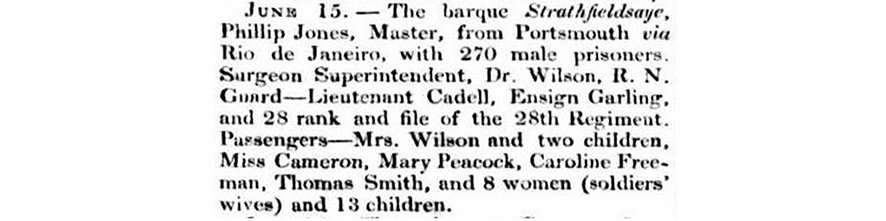

On 15 June1836, with his health largely unaffected by his imprisonment and the long sea voyage, William finally reached New South Wales, the place that was to remain William's home for the rest of his life.[11] What a shocking revelation it must have been for 19-year-old William to realise that he would never see his family or friends ever again.

Announcement, arrival of the convict ship Strathfieldsaye, 1836 [vi]

Soon after landing, William received traditional convict garb and a record was made of his physical description, including a tattoo of ‘several blue dots on back of left hand’; tattoos were common among transported convicts, often a reminder of homes and loved ones left behind.[12]

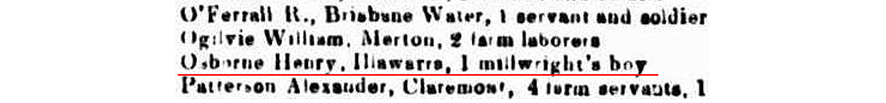

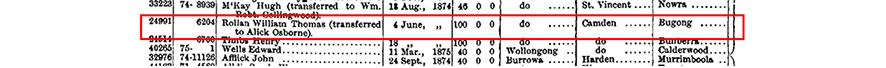

Of greater significance, however, was the change in the record of William's crime. On the hulk Leviathan recorded as ‘Warehouse Br[eakin]g’, William’s New South Wales indenture lists his crime as ‘Stealing linen’; here, too, was the first mention of William's profession - 'Millright's boy'.[13] It is unclear whether this was merely a transcription error or whether William, himself, had promulgated this information to receive greater leniency and a less brutal assignment. Regardless, William’s run of good luck continued when he became assigned to ‘Osborne Henry, Illawarra’ in June 1836.[14]

Convict Indent, 1836 [vii}

Irish by birth and of significant means, Henry Osborne was a prominent landholder in the Illawarra region and, together with his brothers John and Alick, wielded great influence over the area.[15] Undoubtedly the work of the Osborne family, William’s freedom was sealed by a Royal Warrant Pardon. Issued in January 1844, the Pardon formally recognised William's good behaviour only 8 short years into his life sentence.[16]

Despite his pardon stipulating that he remain in New South Wales, William was now a free man.

Read about William Rollan's path to freedom here

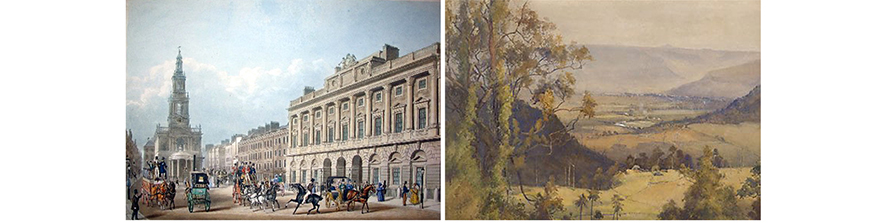

The stark contrast between industrial Lambeth and the Illawarra bush with its rolling hills must have been confronting for William.

Somerset House, England, 1836 [viii]

Kangaroo Valley, New South Wales, 1891 [ix]

It was his isolation in Kangaroo Valley, though, that encouraged William to build relationships with the local Aboriginal people, among them Susan Ellis and her father Dr Ellis, a local well-respected botanist.[17]

William and Susan produced several children together, but it was a fraught partnership.[18] In September 1880, Alick Osborne gave evidence in a Land Court hearing that William’s wife did ‘not always live with him’. In his own evidence, William referred to himself as a ‘single man’.[19] The purpose of the hearing - to determine the validity of William’s claim to 100 acres in the Illawarra region - demonstrated the new direction William had taken after receiving his freedom – that of land selector.[20]

Announcement of land court hearing, 1880 [x]

Despite his early aberration back in England, William became a well-respected member of the Kangaroo Valley community and formed long-standing relationships with local families such as the Osbornes, the Lidbetters and the Chitticks.[21]

Sadly, in 1888, William’s hard-earned good name became sullied by son Robert Rollan aka Towney following in William’s early criminal footsteps. [22] The intense loneliness of living in such an isolated community, too, may have contributed to William turning to drink, and a charge of ‘Drunk & Dis[orderly' in 1895 put a fresh blot on William’s otherwise unblemished record.[23]

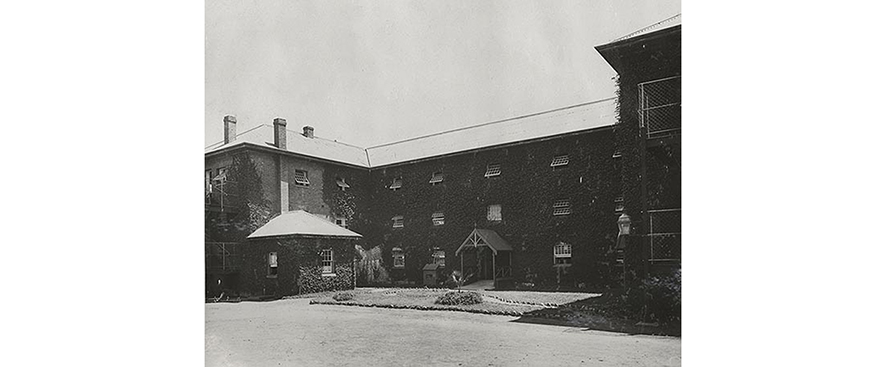

Whatever the reason, in 1899 at the age of 81, William finally passed away from alcohol-related causes at Parramatta Asylum.[24]

George Street Asylum, Parramatta, before 1936 [xi]

Even so, William’s legacy remains a proud one. William Rollan’s contribution to the community of Kangaroo Valley and his union with Susan Ellis that produced many descendants highly skilled in music, art and culture, are worthy reminders of a transported convict who became a model citizen in a new and alien land.[25]

Credits and References

[i] [Metal handcuffs], photograph by Dear McNicoll. National Museum of Australia.. http://collectionsearch.nma.gov.au/object/109320 Retrieved June 7, 2016.

[ii] [Powerloom weaving in 1835] by T. Allom. Last modified March 31, 2016. Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved June 10, 2016. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9430141

[iii] [Old Bailey] 1808, by Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Pugin. Rudolph Ackermann, William Henry Pyne and William Combe, 1904, in The Microcosm of London: or, London in Miniature, Volume 2, London: Methuen and Company. Last modified January 28, 2015. Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved January 9, 2009.https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=566832

[iv] [Prison hulk loading], by Samuel Atkins (1787–1808). Rex Nan Kivell Collection. National Library of Australia: an5601463. Retrieved June 10, 2016. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135231236/view

[v] Ancestry.com. UK, Royal Navy Medical Journals, 1817-1857 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Original data: Admiralty and predecessors: Office of the Director General of the Medical Department of the Navy and predecessors: Medical Journals. ADM 101, 804 bundles and volumes. Records of Medical and Prisoner of War Departments. Records of the Admiralty, Naval Forces, Royal Marines, Coastguard, and related bodies. The National Archives. Kew, Richmond, Surrey. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

[vi] Trove. ‘Shipping Intelligence. ARRIVALS.’ (1836, June 17). The Australian (Sydney, NSW: 1824 – 1848), p. 2. Retrieved June 10, 2016. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article36857156

[vii] Trove. ‘Colonial Secretary’s Office, Sydney, 3rd August, 1836.’ (1836, August 6). The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales (NSW: 1803 – 1842), p. 4. Retrieved June 10, 2016. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page502461

[viii] [Somerset House by Anon publ Ackermann & Co 1836]. Last modified December 29, 2014. Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved June 10, 2016. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=551457

[ix] [Kangaroo Valley, New South Wales] 1891, by A Henry Fullwood (1863-1930). Art Gallery of New South Wales, accession no. 114. Retrieved June 10, 2016. http://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/114/?tab=details

[x] Find My Past. New South Wales, Australia, Government Gazettes, 1853-1899 [database on-line]. Sydney, NSW: Hayes Knight (NSW) Pty. Ltd., 2010. Original data: New South Wales Government Gazette. Assorted volumes, 1853-`899. 1880. p. 603. State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

[xi] [George Street Asylum/State Hospital and Home for Age and Inform Men, Parramatta], before 1937, by Photographic Collection from Australia. Creative Commons Attribution by 2.0. Retrieved July 8, 2016. http://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22350334

[1] Bursill, Leslie William (Les), 'My Family History.' Ecopsychology: Advances From the Intersection of Psychology and Environmental Protection Volume 1 Science and Theory, edited by Darlyne G. Nemeth, Robert B. Hamilton, and Judy Kuriansky, Westport: ABC-CLIO, 2015, pp. 181-183. Retrieved June 10, 2016. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=76xmCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA181&lpg=PA181&dq=ecopsychology+ advances+%22my+family+history%22&source=bl&ots=uITTswO4VT&sig=RISrh5TccuNC6kQxAmy8W1pqGXM&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi7urftoZ_NAhXmIaYKHYKaC78Q6AEIIzAA#v=onepage&q=ecopsychology%20advances %20%22my%20family%20history%22&f=false

[2] Bursill, Leslie William (Les), 'My Family History.'; Bursill, Les and Kurranulla Aboriginal Corporation, Dharawal: the story of the Dharawal speaking people of Southern Sydney: a collaborative work, Sydney: Kurranulla Aboriginal Corporation, 2007, p. 62. Retrieved June 10, 2016.http://lesbursill.com/site/PDFs/_Dharawal_4Sep.pdf

[3] Les Bursill, telephone interviews with Sandra Kerkvliet, May and June, 2016.

[4] FamilySearch.org. England Births and Christenings, 1538-1975, [database on-line]. Salt Lake City, UT, USA: Intellectual Reserve, Inc., 2014. Reference Item 2, p. 746. FHM Microfilm 1,041,526. William Rollan. Retrieved June 9, 2016. https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:J3L2-2L4

[5] British Museum. ‘The Industrial Revolution and the changing face of Britain’. Retrieved June 10, 2016.http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/publications/online_research_catalogues/paper_money/

paper_money_of_england__wales/the_industrial_revolution.aspx; Wikipedia. ‘Industrial Revolution’. Last modified June 7, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2016.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrial_Revolution

[6] Old Bailey Proceedings Online, ver. 7.2, June 9, 2016. Trial of William Rollan. November 23, 1835, pp. 167-169. Retrieved June 10, 2016. http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t18351123-179

[7] Old Bailey Proceedings Online. Trial of William Rollan.

[8] Ancestry.com. UK, Prison Hulk Registers and Letter Books, 1802-1849 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Home Office: Convict Prison Hulks: Registers and Letter Books, 1802-1849. Microfilm, HO9, 5 rolls. The National Archives, Kew, England. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

[69 Find My Past. Convict Transportation Registers, 1787-1870 [database on-line]. Sydney, NSW: Hayes Knight (NSW) Pty. Ltd., 2010. Original data: Home Office: Convict Transportation Registers, 1787 – 1870. Microfilm, HO11. The National Archives, Kew, England, Retrieved June 10, 2016.

[10] Ancestry.com. UK, Royal Navy Medical Journals, 1817-1857 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Original data: Admiralty and predecessors: Office of the Director General of the Medical Department of the Navy and predecessors: Medical Journals. ADM 101, 804 bundles and volumes. Records of Medical and Prisoner of War Departments. Records of the Admiralty, Naval Forces, Royal Marines, Coastguard, and related bodies. The National Archives. Kew, Richmond, Surrey. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

[11] Trove. ‘Shipping Intelligence. ARRIVALS.’ (1836, June 17). The Australian (Sydney, NSW: 1824 – 1848), p. 2. Retrieved June 10, 2016. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article36857156

[12] Ancestry.com. New South Wales, Australia, Convict Indents, 1788-1842 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Original data: New South Wales Government. Annotated printed indents (i.e., office copies), NRS 12189. Microfiche 696–730, 732–744. State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

[13] Ancestry.com. New South Wales, Australia, Convict Indents, 1788-1842.

[14] Ancestry.com. New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia Convict Musters, 1806-1849 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007. Original data: Home Office: Settlers and Convicts, New South Wales and Tasmania. Microfilm HO10, Pieces 5, 19-20, 32-51. The National Archives of the UK (TNA), Kew, Surrey, England. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

[15] Osborne, Frank, 'Alick Osborne and the Adam Lodge'. Illawarra Historical Society Bulletin, March 1998, pp. 6-14. Retrieved June 12, 2016. http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2072&context=ihsbulletin; Osborne, P.J.B., 'Osborne, Henry (1803–1859)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 2, 1967. Retrieved June 9, 2016. http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/osborne-henry-2527

[16] Ancestry.com. New South Wales, Australia, Convict Registers of Conditional and Absolute Pardons, 1788-1870 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. Original data: Copies of Royal Pardon Warrants. Series 1161. State Records Reel 772, copy of 4/4495, pp. 168-169. State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

[17] Bursill, Leslie William (Les), 'My Family History.'; Macarthur-Onslow, Annette, ‘DR ELLIS, BOTANIST’,Illawarra Historical Society Bulletin, June 1983, p. 30. Retrieved June 11, 2016.http://ro.uow.edu.au/viewcontent.cgi?article=1647&context=ihsbulletin

[18] Bursill, Leslie William (Les), 'My Family History.'

[19] Trove. ‘Land Court.’ (1880, September 9). The Telegraph and Shoalhaven Advertiser (NSW: 1879 – 1881),

p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article132980756

[120 Trove. ‘Land Court.’ (1880, September 9).

[21] Les Bursill, e-mail message to Sandra Kerkvliet, June 9, 2016.

[22] Ancestry.com. New South Wales, Australia, Gaol Description and Entrance Books, 1818-1930 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012. Roll: 285. State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

[22] Trove. ‘Kangaroo Valley Court of Petty Sessions.’ (1888, May 30). Shoalhaven Telegraph (NSW: 1881 – 1937), p. 2. Retrieved June 10, 2016. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article135355039

[24] Les Bursill, telephone interviews; NSW Death Certificate District of Parramatta 10545/1899. William Rollan.

[25] Les Bursill, telephone interviews.